Forests are not a metaphor

exploitation myths vs. sci-fi-fantasy fiction

Forests hold worlds together—both real and imagined. They shape our myths, and in turn, those myths shape how we perceive and relate to them. Sometimes, when I’m deep in a work of fiction, I catch glimpses of real ecological entanglements: moments in a story that reveal magical ways of perceiving or recognizing the natural world. When that happens, it feels as though the narrative is metabolizing something real, translating the ecological into something legible to the heart.

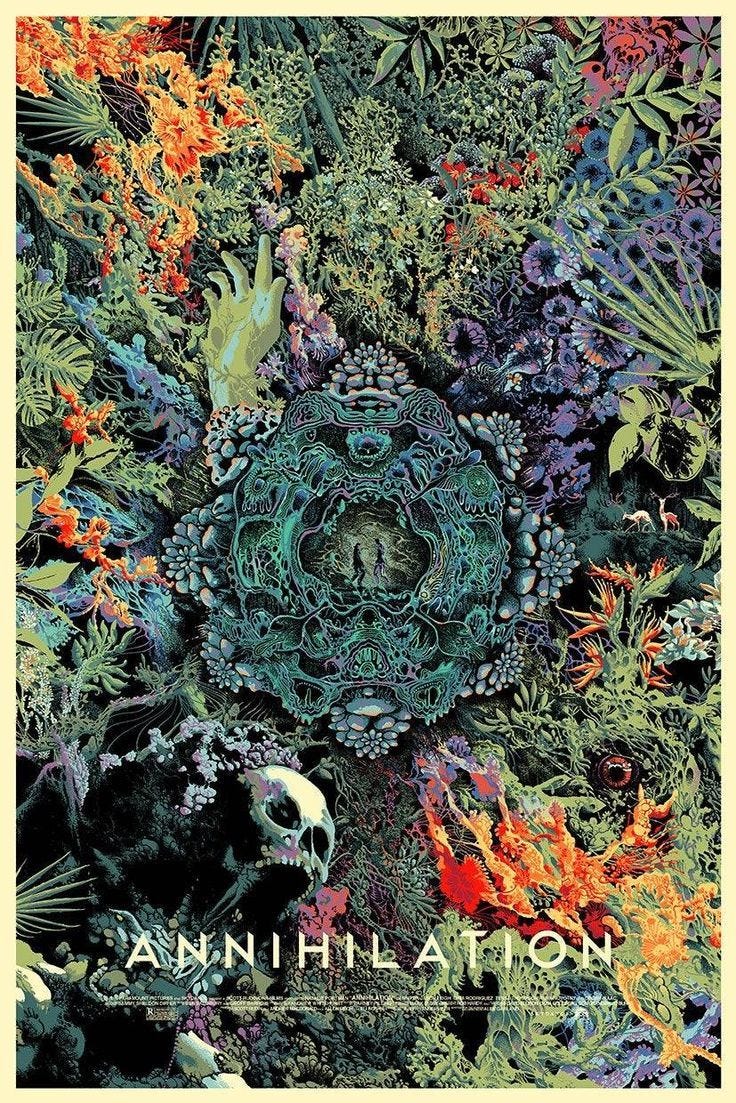

From the unnerving mysteriousness of Fangorn Forest in Lord of the Rings to the raging wildfires in Parable of the Sower, fantasy forests play an important role in revealing narrative tensions and supernatural encounters. But before I wind down a road of sci-fi/fantasy fiction, and its depiction of climate scenarios, I’d like to mention a popular colonial–fantasy fiction—a myth that plays out in the real world.

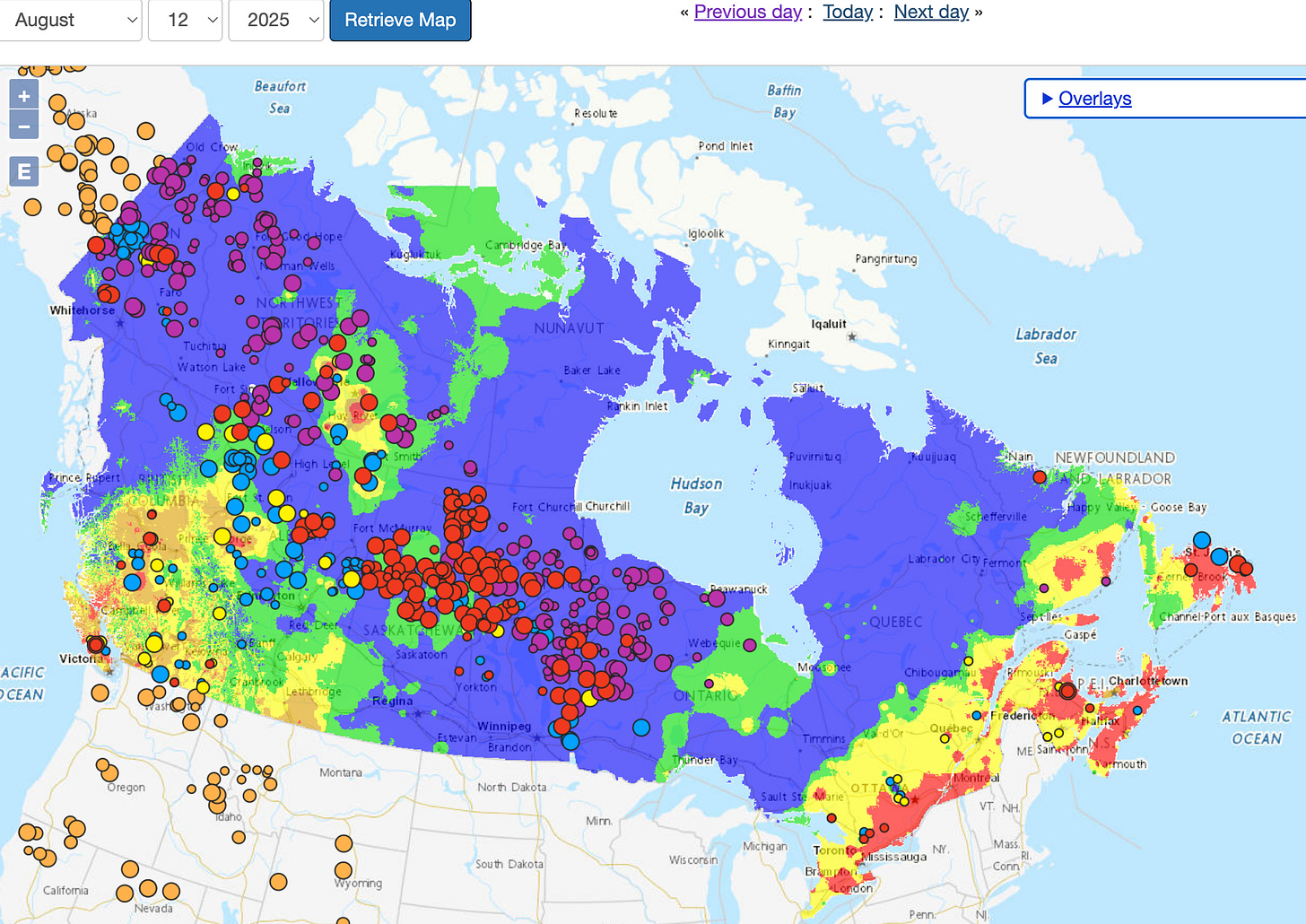

Extraction without reciprocation is a form of debt. Under the name of “resources,” forests become parcels of individual trees that are cut, counted, and restocked, essentially reduced to their timber yield. This two-dimensional picture lacks the depth of context or ecological imagination. And right now, that ecological debt is inflamed. Over 700 wildfires are burning across my home country of Canada as I write this in August 2025. And over 300 of them are deemed “out of control” by the Canadian Wildland Fire Information System.

For many, especially those living in cities or industrial landscapes stripped of biodiversity, wildness is not a focal point of daily life. So what happens to the collective imagination when wildness is suppressed, paved over, or rendered invisible? Well, through colonial-fantasy-thinking nature is rendered passive, replaceable, and infinitely harvestable. For generations however, indigenous communities have maintained that this is a false paradigm.

So how do we respond to the realities of deforestation and its role in climate collapse in a time of both misinformation and myth-making? Can the fictions of industrial lobbyists be usurped by the fictions of ecologically-driven sci-fi fantasy? Perhaps both the problem and the answers lie partly in the stories that forefront ecological collaboration—especially ones that teach us to live in right-relationship with biodiverse ecosystems.

Canada’s worsening wildfire situation is a recipe that congeals around industrial extraction industries. In British Columbia—a province nearly twice the size of France—only 2% of old growth remains. The other 98% of these ancient ecosystems have been logged, many on repeat. Tree planting functions well within this extractive system, while monoculture replanting and long-term fire suppression have worsened biodiversity and weakened natural regeneration cycles.

Indigenous cultures have long recognized trees and non-human beings as kin—imbued with agency, presence, and spirit. When communities were forcibly removed from their territories and their stewardship practices—including ceremonial firekeeping—were outlawed or suppressed, this economy of reciprocity was disrupted. This disruption paved the way for extractive systems that reclassified the land as mere “resource” rather than living kin.

These narratives long predate our modern hyperfixation on growth and development. That’s not just poor ecological thinking—it’s a tired blueprint for colonial-fantasy-fiction. And frankly, it’s boring as hell.

In reality, old, evolved, and complex ecosystems can withstand myriad disturbances—fire included. These natural disturbances, alongside the presence of native fungi, plants, animals, and humans who care for the land can actually increase resilience to climate change. We’re seeing examples of this in the rise of regenerative agriculture, farming and even forestry. This is because a healthy forest is also a functional community.

In many stories, forests operate as sites of moral reckoning, memory, and transformation. The woods are where the old world ends and something else—stranger, truer, or more dangerous—begins. In The Lord of the Rings, Fangorn Forest is not just ancient—it’s alive, slow-moving, and deeply wise. Ents (or tree shepherds) like Treebeard are sentient beings who have lived through eras of magic, war and deforestation. They serve as witnesses and guardians of memory (though perhaps slow on the recall). When the Ents rise to fight the power-obsessed Saruman—it is an act of resistance. The forest fights back.

In Parable of the Sower, Octavia Butler weaves wildness, danger, and survival into a post-apocalyptic Californian landscape (an increasingly familiar landscape amidst ICE raids and wildfires in LA). The forest becomes both refuge and test. As the protagonist Lauren Olamina walks north through burning towns and looted farmland, she remakes her relationship to land, danger, and community, establishing the Earthseed religion whose mantra is “God is change”. Survival here is not about domination, but connection and compassionate leadership.

In N.K. Jemisin’s Broken Earth trilogy, the Earth itself is alive—angry, grieving, sentient. In The Fifth Season we learn that the earth’s minerals are alive, like veins embedded in the earth's crust. Throughout the trilogy characters can feel and manipulate geological and ecological forces. The series begins after ecological collapse—and characters reckon with the cost of that breakdown, with parts of the world even killing or persecuting those who commune with the ‘evil Earth’.

In Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Word for World Is Forest, a lush forested planet is colonized by humans who extract wood and enslave the native Athsheans. The Athsheans, who live in harmony with the forest and dream collectively, are driven to violent resistance. The forest becomes a mirror and a battleground—between colonial delusion and indigenous knowledge, between domination and collective dreaming.

Even Harry Potter, a franchise not often praised for ecological consciousness, uses the Forbidden Forest as a moral testing ground. It’s where subjugated magical creatures gather, truths are uncovered, loyalties tested, and cheap hacks to immortality are found i.e. unicorn blood as ‘resource’. The Whomping Willow, a magical bouncer—not to be fucked with.

In all these stories, forests are more than backdrops. They are agents. They hold wisdom, demand response, and become catalysts for story and character development.

Yet in our collective imagination, forests are often fixed as mysterious, unknowable—symbols of wildness or the unconscious. When we treat forests as metaphor alone, we overlook their material truths as living, breathing systems that sustain life on Earth.

As living networks, forests hold entire lineages of interspecies relationships. Stories of intergenerational magic can be found in real forests.

Canadian forest ecologist Susan Simard’s groundbreaking work Finding the Mother Tree revealed how trees communicate and share resources through mycelial networks—underground fungal threads that act like a forest’s brain, linking ecosystems together. These findings have reshaped how we understand kinship, cooperation, and intelligence in nature. According to the Scientific Alliance for Forest Transformation (SAFT), intact forest ecosystems are among our most effective tools for climate mitigation1. Despite numerous widely accredited studies2, governments are pouring billions into “new” carbon sequestration tech, whilst ignoring indigenous rights, old-growth protection and biodiversity restoration.

During a forest ecology workshop I co-organized a few years ago, forest ecologist Dr. Rachel Holt offered me some advice I’ve thought about many times since. Her goal, she said, is to spend as much time in forests as possible—and to answer as few emails as possible. “Otherwise,” she said, “you burn out.”

That idea stuck with me.

Maybe human burnout is inseparable from ecological burnout? Maybe we are not fully capable of reflecting on ourselves without some form of fiction. Through capitalist myths, we are encouraged to seek inspiration in all the wrong places. Mirror, mirror on the wall—who is the most successful of them all? Like Frodo gazing into Galadriel’s mirror, we see his community engulfed in flame. When I look at my phone, I see the same.

If stories shape culture—and forests shape climate—then we need stories that do both. Not for nostalgia. Not for metaphor. But for survival.

Sources

J.R.R. TolkienOctavia E. ButlerN.K. JemisinUrsula K. Le GuinStark, H.K. (2012). “Ishkode as spirit and heart — Anishinaabe worldview.” SAGE Journals.Maamwi Anjiakiziwin: Firekeeping roles within Anishinaabe culture; ecological stewardship. maamwigeorgianbay.caHemens, A. (2025). “Syilx Okanagan cultural burning and firekeepers.” IndigiNews.Centering Indigenous Voices: The Role of Fire in the Boreal Forest of North America. (July 2022). Current Forestry Reports. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007

SAFT www.saftforestry.com

naturecreativecommons.org/resources